Partial Correlations (R,Python)

Red means that the page does not exist yet

Gray means that the page doesn’t yet have separation of different levels of understanding

Orange means that the page is started

In this website you can choose to expand or shrink the page to match the level of understanding you want.

- If you do not expand any (green) subsections then you will only see the most superficial level of description about the statistics. If you expand the green subsections you will get details that are required to complete the tests, but perhaps not all the explanations for why the statistics work.

- If you expand the blue subsections you will also see some explanations that will give you a more complete understanding. If you are completing MSc-level statistics you would be expected to understand all the blue subsections.

- Red subsections will go deeper than what is expected at MSc level, such as testing higher level concepts.

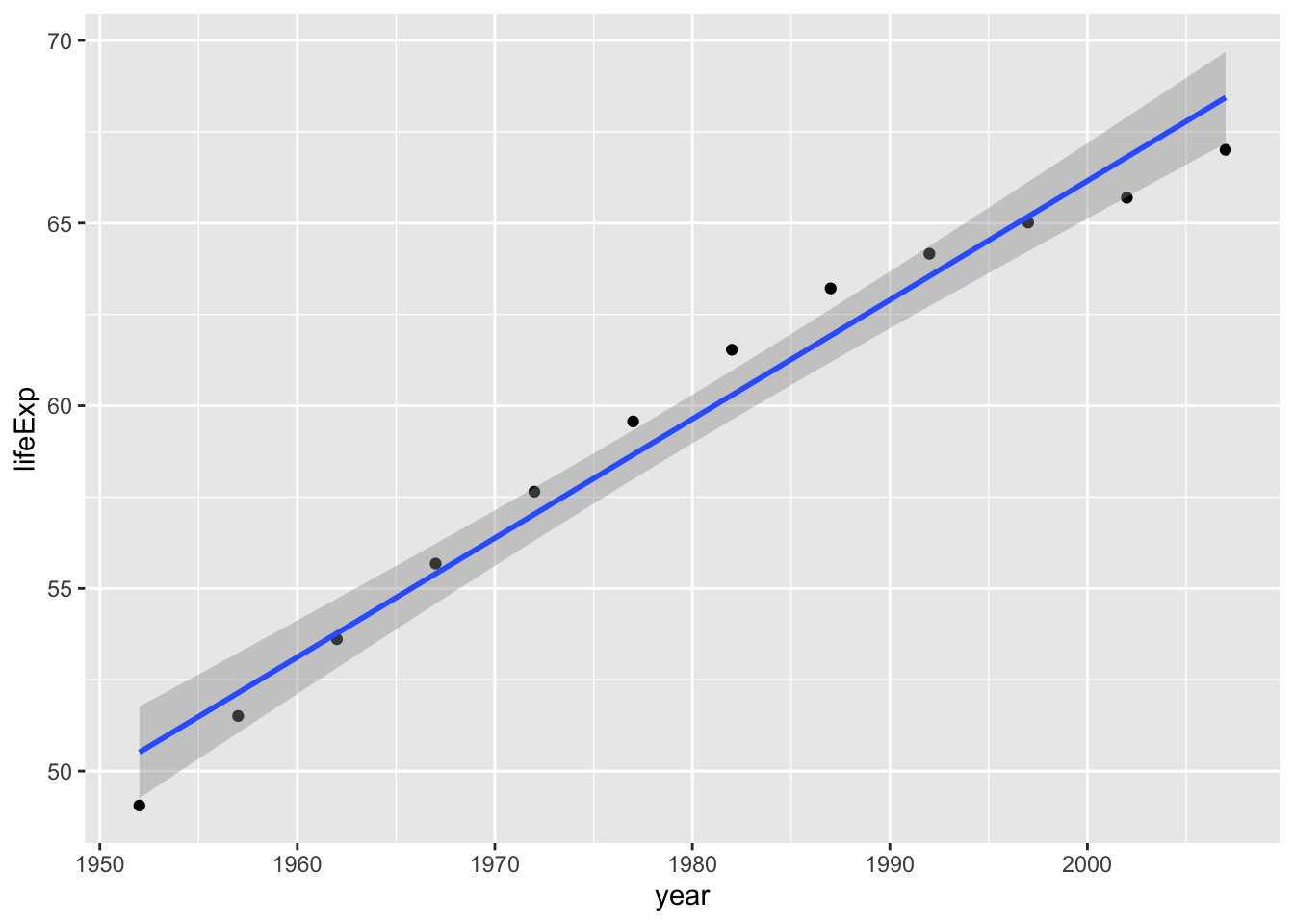

As you may have heard, correlation does not equal causation. One possible reason for this is that there’s a third variable that explains an association. Let’s imagine that we are trying to understand whether life expectancy goes up over time and why. First of all, let’s check if lifeExpectancy is going up over time using the gapminder data:

library(gapminder)

library(ggplot2)

library(tidyverse)── Attaching core tidyverse packages ──────────────────────── tidyverse 2.0.0 ──

✔ dplyr 1.1.3 ✔ readr 2.1.4

✔ forcats 1.0.0 ✔ stringr 1.5.0

✔ lubridate 1.9.3 ✔ tibble 3.2.1

✔ purrr 1.0.2 ✔ tidyr 1.3.0

── Conflicts ────────────────────────────────────────── tidyverse_conflicts() ──

✖ dplyr::filter() masks stats::filter()

✖ dplyr::lag() masks stats::lag()

ℹ Use the conflicted package (<http://conflicted.r-lib.org/>) to force all conflicts to become errorsgapminder %>%

group_by(year) %>%

summarise(

lifeExp = mean(lifeExp),

gdpPercap = mean(gdpPercap)

) -> gapminder_by_year

cor.test(gapminder_by_year$year, gapminder_by_year$lifeExp)

Pearson's product-moment correlation

data: gapminder_by_year$year and gapminder_by_year$lifeExp

t = 18.808, df = 10, p-value = 3.91e-09

alternative hypothesis: true correlation is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

0.9498070 0.9962336

sample estimates:

cor

0.986158 ggplot(data = gapminder_by_year, aes(x = year, y = lifeExp)) +

geom_point() +

geom_smooth(method = lm, formula = 'y ~ x')

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

from scipy.stats import pearsonr

from gapminder import gapminder

gapminder_by_year = gapminder.groupby('year').agg({'lifeExp': 'mean', 'gdpPercap': 'mean'}).reset_index()

print(gapminder_by_year)

correlation, p_value = pearsonr(gapminder_by_year['year'], gapminder_by_year['lifeExp'])

print("Correlation coefficient:", correlation)

print("p-value:", p_value)

sns.scatterplot(data=gapminder_by_year, x='year', y='lifeExp')

sns.regplot(data=gapminder_by_year, x='year', y='lifeExp')

plt.xlabel('Year')

plt.ylabel('Life Expectancy')

plt.show()So now that we’ve confirmed that there is a positive association between the year and life expectancy, the next question is why? What changes from year to year that could explain increased life expectancy? Let’s investigate whether gdp per capita generally goes up each year, and whether it’s associated with life expectancy. If both of these things are true, then perhaps the increase in gdp per year is an explanation of the association between year and life expectancy.

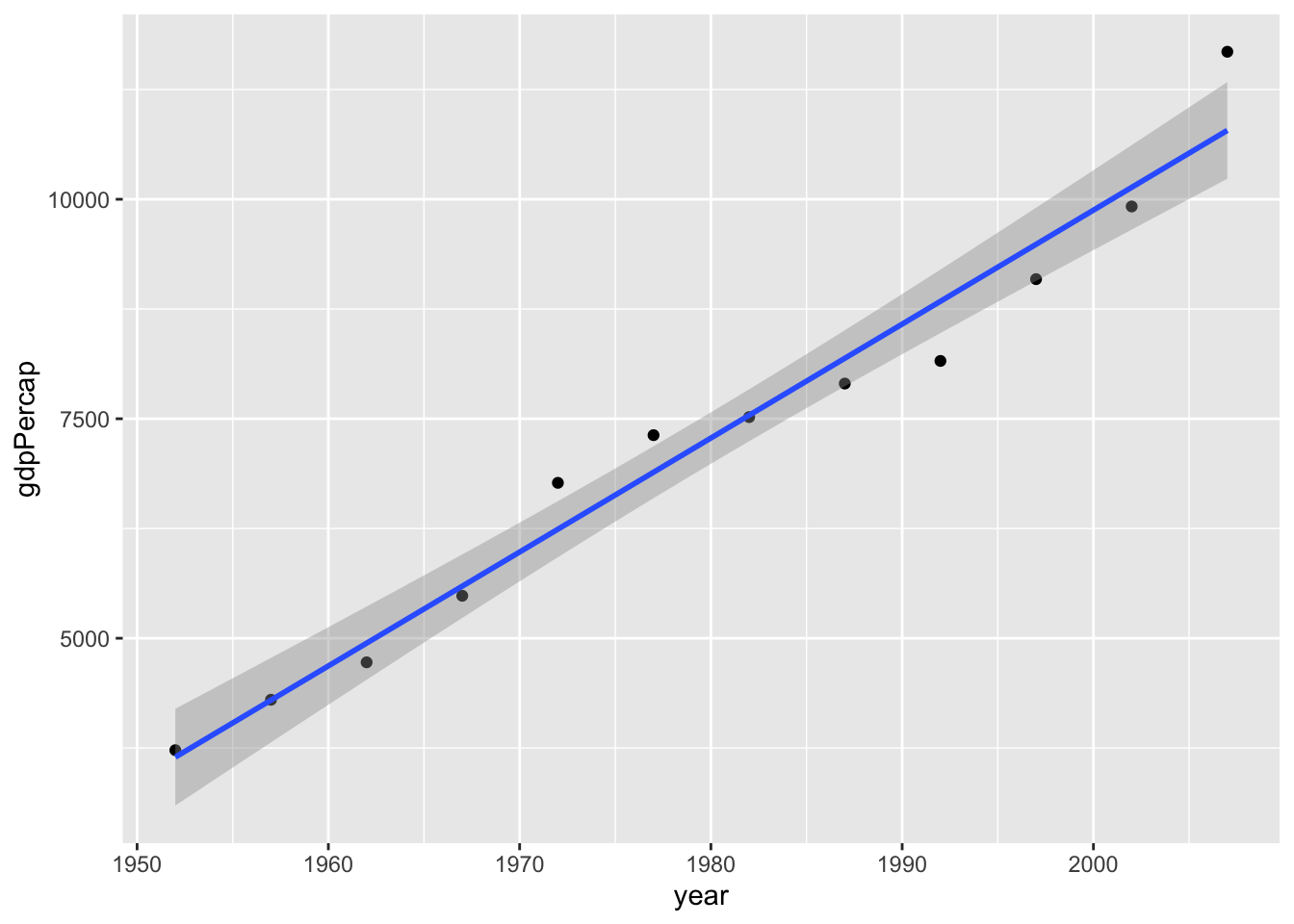

Is year and gdp per capita associated?

cor.test(gapminder_by_year$year, gapminder_by_year$gdpPercap)

Pearson's product-moment correlation

data: gapminder_by_year$year and gapminder_by_year$gdpPercap

t = 17.039, df = 10, p-value = 1.022e-08

alternative hypothesis: true correlation is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

0.9393538 0.9954265

sample estimates:

cor

0.9832101 ggplot(data = gapminder_by_year, aes(x = year, y = gdpPercap)) +

geom_point() +

geom_smooth(method = lm, formula = 'y~x')

correlation, p_value = pearsonr(gapminder_by_year['year'], gapminder_by_year['gdpPercap'])

print("Correlation coefficient:", correlation)

print("p-value:", p_value)

sns.scatterplot(data=gapminder_by_year, x='year', y='gdpPercap')

sns.regplot(data=gapminder_by_year, x='year', y='gdpPercap')

plt.xlabel('Year')

plt.ylabel('gdpPercap')

plt.show()Whilst there are some outliers in earlier years, we seem to have found that gdp per capita has gone up.

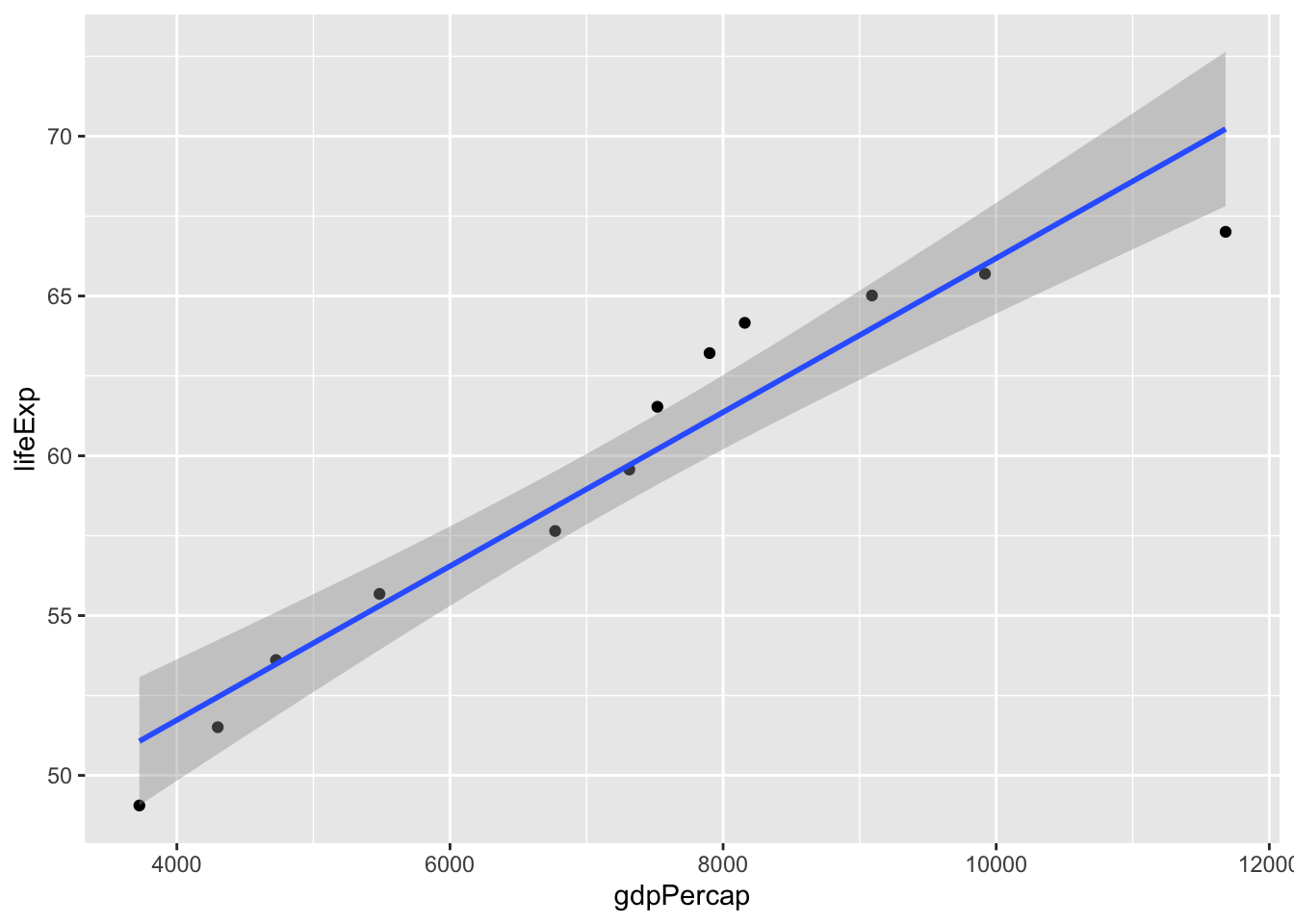

Is gdp per capita and life expectancy associated?

cor.test(gapminder_by_year$gdpPercap, gapminder_by_year$lifeExp)

Pearson's product-moment correlation

data: gapminder_by_year$gdpPercap and gapminder_by_year$lifeExp

t = 11.137, df = 10, p-value = 5.875e-07

alternative hypothesis: true correlation is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

0.8663785 0.9895601

sample estimates:

cor

0.9619721 ggplot(data = gapminder_by_year, aes(x = gdpPercap, y = lifeExp)) +

geom_point() +

geom_smooth(method = lm, formula = 'y ~ x')

# Perform correlation test between gdpPercap and lifeExp

correlation, p_value = stats.pearsonr(gapminder_by_year['gdpPercap'], gapminder_by_year['lifeExp'])

# Print the correlation coefficient and p-value

print("Correlation coefficient:", correlation)

print("p-value:", p_value)

# Create scatter plot with regression line

sns.scatterplot(data=gapminder_by_year, x='gdpPercap', y='lifeExp')

sns.regplot(data=gapminder_by_year, x='gdpPercap', y='lifeExp', scatter=False)

plt.xlabel('GDP per capita')

plt.ylabel('Life Expectancy')

plt.show()So the above analysis suggests that all three variables are incredibly related. (you are unlikely to see such strong associations in real psychology experiments). But let’s now check in whether there’s still an association between the year and life expectancy once you control for GDP per capita. This partial correlation can be visualised as follows:

To calculate the partial correlation r value you control for the association between the two variables

\[ r_{xy*z} = \frac{r_{xy} - r_{xz} * r_{yz}}{\sqrt{(1-r^2_{xz})(1-r^2_{yz})}} = \frac{originalCorrelation - varianceExplainedByCovariate}{varianceNotExplainedByCovariate} \]

- \(x\) = The Year

- \(y\) = Life expectancy

- \(z\) = GDP per capita

- \(\sqrt{1- r^2_{xz}}\) = variance not explained by correlation between Year(\(x\)) and GDP (\(z\))

- \(\sqrt{1- r^2_{yz}}\) = variance not explained by correlation between Life Expectancy (\(y\)) and GDP (\(z\))

One way to think of the formula above is that: - the top-half represents how much variance is explained by overlap between the two main variables, subtracted by the variance of each variable with the confound - the bottom-half represents how much variance there is left to explain once you’ve removed associations between each main variable and the covariate.

Let’s see what the r value is after this partial correlation:

\[ r_{xy*z} = \frac{r_{xy} - r_{xz} * r_{yz}}{\sqrt{(1-r^2_{xz})(1-r^2_{yz})}} = \frac{.986158 - .9832101 * .9619721 }{\sqrt{(1-.9832101^2)(1-.9619721^2)}} = \frac{.040354}{.04984321} = .8092841 \]

Let’s check if the manually calculated partial r-value is the same as what R gives us:

library(ppcor)Loading required package: MASS

Attaching package: 'MASS'The following object is masked from 'package:dplyr':

selectpcor(gapminder_by_year)$estimate

year lifeExp gdpPercap

year 1.0000000 0.8092844 0.7629391

lifeExp 0.8092844 1.0000000 -0.2521280

gdpPercap 0.7629391 -0.2521280 1.0000000

$p.value

year lifeExp gdpPercap

year 0.000000000 0.00254769 0.006309324

lifeExp 0.002547690 0.00000000 0.454498736

gdpPercap 0.006309324 0.45449874 0.000000000

$statistic

year lifeExp gdpPercap

year 0.000000 4.1331001 3.5404830

lifeExp 4.133100 0.0000000 -0.7816358

gdpPercap 3.540483 -0.7816358 0.0000000

$n

[1] 12

$gp

[1] 1

$method

[1] "pearson"import pingouin as pg

# Calculate partial correlation with p-values, estimates, and statistics

partial_corr1 = pg.partial_corr(data=gapminder_by_year, x="gdpPercap", y="lifeExp", covar="year", method='pearson')

partial_corr2 = pg.partial_corr(data=gapminder_by_year, x="year", y="gdpPercap", covar="lifeExp", method='pearson')

partial_corr3 = pg.partial_corr(data=gapminder_by_year, x="lifeExp", y="year", covar="gdpPercap", method='pearson')

coef1 = partial_corr1['r'].values[0]

coef2 = partial_corr2['r'].values[0]

coef3 = partial_corr3['r'].values[0]

p_value1 = partial_corr1['p-val'].values[0]

p_value2 = partial_corr2['p-val'].values[0]

p_value3 = partial_corr3['p-val'].values[0]

# Create a matrix

matrix1 = np.zeros((3, 3))

# Assign the interaction values

matrix1[0, 1] = coef3

matrix1[1, 0] = coef3

matrix1[0, 2] = coef2

matrix1[2, 0] = coef2

matrix1[1, 2] = coef1

matrix1[2, 1] = coef1

# Set the diagonal to 1

np.fill_diagonal(matrix1, 1)

# Create a DataFrame from the matrix

matrix_coef = pd.DataFrame(matrix1, columns=['year', 'lifeExp', 'gdpPercap'], index=['year', 'lifeExp', 'gdpPercap'])

# Create a matrix

matrix2 = np.zeros((3, 3))

# Assign the interaction values

matrix2[0, 1] = p_value3

matrix2[1, 0] = p_value3

matrix2[0, 2] = p_value2

matrix2[2, 0] = p_value2

matrix2[1, 2] = p_value1

matrix2[2, 1] = p_value1

# Set the diagonal to 1

np.fill_diagonal(matrix2, 1)

# Create a DataFrame from the matrix

matrix_p_val = pd.DataFrame(matrix2, columns=['year', 'lifeExp', 'gdpPercap'], index=['year', 'lifeExp', 'gdpPercap'])

# Print the resulting matrix

print(matrix_p_val)

# Print the resulting matrix

print(matrix_coef)Yes, the pearson correlation between year and life expectancy is .8092844, so the difference of .0000003 is a rounding error from the manual calculations above. Just to confirm that this is a rounding error, here’s what you get if you complete the same steps but with the estimate part of the correlation objects instead:

x.y.cor <- cor.test(gapminder_by_year$year, gapminder_by_year$lifeExp)

x.z.cor <- cor.test(gapminder_by_year$year, gapminder_by_year$gdpPercap)

y.z.cor <- cor.test(gapminder_by_year$gdpPercap, gapminder_by_year$lifeExp)

(x.y.cor$estimate - x.z.cor$estimate * y.z.cor$estimate)/sqrt((1-x.z.cor$estimate^2) * (1 - y.z.cor$estimate^2)) cor

0.8092844 import scipy.stats as stats

import numpy as np

# Calculate correlation coefficients

x_y_cor = stats.pearsonr(gapminder_by_year['year'], gapminder_by_year['lifeExp'])[0]

x_z_cor = stats.pearsonr(gapminder_by_year['year'], gapminder_by_year['gdpPercap'])[0]

y_z_cor = stats.pearsonr(gapminder_by_year['gdpPercap'], gapminder_by_year['lifeExp'])[0]

# Calculate the desired value

result = (x_y_cor - x_z_cor * y_z_cor) / np.sqrt((1 - x_z_cor**2) * (1 - y_z_cor**2))

# Print the result

print(result)Confirming that the difference in the manual calculation is a rounding error. Note that the numbers you get from R may be rounded numbers, and so your calculations may reflect the rounding.

To conclude, as there is still an association between Year and Life Expectancy once controlling for GDP, this partial correlation is consistent with GDP not being the only explanation for why Life Expectancy goes up each year.

Question 1

What does a variable need to correlate with to be a viable candidate as a covariate?